AIM13 Commentary - 2019 Q4

“Investing isn’t about beating others at their game.

It’s about controlling yourself at your own game.”

Risk awareness has always been at the center of our investment strategy, yet after nearly eleven years of almost unabated positive equity market returns, the discipline required to maintain a focus on risk is difficult for most investors to sustain. With the S&P 500 Total Return index (“S&P 500 TR”) up over 31% in 2019, capping the first decade without a recession and one where the S&P 500 TR posted an annualized return of 13.6%, many investors have lost sight of real risk. Risk is currently viewed in terms of identifiable episodes that come and go – think the coronavirus, war with Iran, Brexit, or a trade dispute with China – rather than a constant of which investors must always be vigilant. The problem with that thinking is that it exposes a portfolio to losses that are far greater than what investors imagine could be possible.

* * *

“You must realize that the greatest weapon you possess is self-control.”

In the current environment, we think that most investors are lying to themselves about their risk tolerance and about how they will react when the markets have a significant pullback. A major cause of this disconnect is people’s inability to look within themselves and to understand their own biases. Our partner, Ambassador Henry Crumpton, wrote at length about this dynamic in his book, The Art of Intelligence. Mr. Crumpton spent nearly 25 years in the CIA, and when he would land in unfamiliar territory, the first thing he did was set his GPS to determine his exact coordinates. Only then, he writes, could he map the surrounding area and chart a course. He uses this observation to make a larger point: “Without a solid, central reference point of yourself, every other assessment and judgment is skewed.” The same can be said about investing. If you do not know who you are and where you are pointed, your biases will prevent an honest assessment of managers or how you will behave during turbulent times.

“If 2000-2009 was the Lost Decade for investors, 2010-2019 was the Decade of Forgetting.”

Unfortunately, investors do not know or at best have forgotten what real risk is. We define risk as how much of our own net worth we are willing to throw off the top of the Sears Tower (we have not adopted its “new” name) – in other words, for us, risk equals the PERMANENT loss of capital. Most investors, however, define risk in other terms, such as volatility, business risk, or on a relative basis, asking themselves how their portfolio performed relative to a benchmark or another investor. In contrast, as long-term investors, we can accept short term price fluctuations in exchange for long-term returns. We also set our own goals – capital preservation and superior risk-adjusted returns over time – without reference to what others are doing or the hottest trends (like bitcoins, gold, etc.).

In addition, views of risk and risk tolerance evolve over time. People at different stages of wealth accumulation view risk differently. However, LPs in funds typically want all of the manager’s liquid net worth in the fund. By doing so, they fail to recognize that when a manager accumulates the majority of their wealth inside the fund they manage over time, the manager’s own investment objectives may change and their appetite for risk may decline. We were once invested with a manager whose significant personal stake in the fund had the effect of almost freezing the manager’s ability to make investments, so fearful was he of losing his own money.

Recent events also disproportionately shape one’s view of risk. The graph below illustrates that since the financial crisis, the risks (measured in terms of market pullbacks) investors have experienced have been episodic and fairly short-lived:

Source of Graph: J.P. Morgan Asset Management

In this regard, the S&P 500’s track record since the financial crisis has conditioned many investors (especially those who were not active in the markets twelve years ago) to believe that they will recoup losses in a fairly short time frame. We see a parallel here with the learned behavior of Ivan Pavlov’s dogs, who were famously conditioned to salivate when they heard a bell ring because they associated it with food. We need to remind people that markets do not always rebound quickly. As the left half of the chart above shows, in the prior twenty years, there have been pullbacks of -49% and -57%, which required recovery periods of approximately six and five years, respectively. Likewise, in our lifetime, there have been two extended periods of flat price returns in the S&P 500 (from 1968 to 1982, and from 1998 to 2011).

The question we have is, how will people react to a sustained pullback? One answer can be found in a more obscure finding of Dr. Pavlov. Many people are not aware that during a massive flood in Leningrad in 1924, the Russian physiologist’s famous dogs were trapped in their cages and many died. Some were required to swim a quarter mile to dry land. Following this traumatic event, many dogs “forgot” their famous conditioning of salivating when they heard the bell ring. Pavlov observed that extreme conditions can cause profound behavioral changes. So too for investors. As we saw with the major shock of 2008, investors tended to “forget” that markets do indeed rise over the long term. Following the financial crisis, many investors were out of the market in 2009-2010 when it began its recovery.

The truth is that most investors today focus on recent experiences and have forgotten that at some point “black swans” will happen. We strive to be aware of all potential risks, although we also know the next big risk may be something we are not thinking of. In May of 2013, in the section of our letter where we talk about what worries us, we wrote about “reports out of China recently from the World Health Organization regarding H7N9 or the mysterious ‘bird flu.’” We quoted Scott Gottlieb at Forbes who wrote at the time, “We’re not prepared for China’s deadly Bird Flu.” The question we ask ourselves is, are investors any better prepared today for the coronavirus? If not, then how are investors prepared for something much worse?

“You sit on a throne of lies!”

As Morgan Housel, a partner at the Collaborative Fund, has written in a series of well-reasoned essays about risk, “people are poor forecasters of their future selves.” In fact, investors lie to themselves about their self-control to see potholes coming and avoid them (“I won’t be greedy”) or exploit them when they arrive (“I’ll see it as an opportunity”). Mr. Housel argues that investors should prepare for risk the same way California prepares for earthquakes. That is, even in the absence of any actionable indication of an imminent catastrophe, you should design your portfolio for a major event so you are prepared to survive it when it happens.

“Most people overestimate what they can do in one year

and underestimate what they can do in ten years.”

We could not have seen bird flu coming in 2013 or the coronavirus epidemic today. Nor could we have predicted 2008. However, a successful long-term investment strategy cannot turn on these types of individual events, small or large. Rather, we must be honest with ourselves and try to exercise the self-discipline it takes to manage real risk over time, and not to drift off course by either smooth sailing (the absence of negative events) or rough seas (the black swans we know will happen). After the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor, the U.S. Navy planted mines in San Francisco Bay and dug trenches along the West Coast. In retrospect, that was a natural over-reaction to an unexpected large-scale event. We must guard against such vacillations in our behaviors and outlook – either overly rosy or excessively guarded. We draw a parallel to something Rodney Faraon, a partner at Crumpton Group, said to us recently: “You shouldn’t waste time and energy trying to predict which truck among thousands will be the one that finally causes a bridge to collapse. Instead, you should examine the fundamental structural weaknesses of that bridge, and then you’ll have a more realistic sense of the risk.” There are limitless risks, but we must come in every day maintaining our focus and looking forward down the road. That is where our “compass” points.

Here are just some of the ways we do that:

Pay attention to details: We recently noticed on our monthly recurring coffee order through Amazon that at the bottom of the email, they included a note about a 25% price increase in just one month:

The experience reminded us of the importance of keeping an eye on the details. As John Wooden said, “Little things make big things happen.” Even though we are inundated with data about our current and focus list managers, we are constantly scouring that information – along with exploring ways to streamline our data collection processes. This is critical because, when it comes to manager risk, in our experience “the devil is in the details.” All too often we have avoided hiring a manager or fired a current one because something small led us to something large.

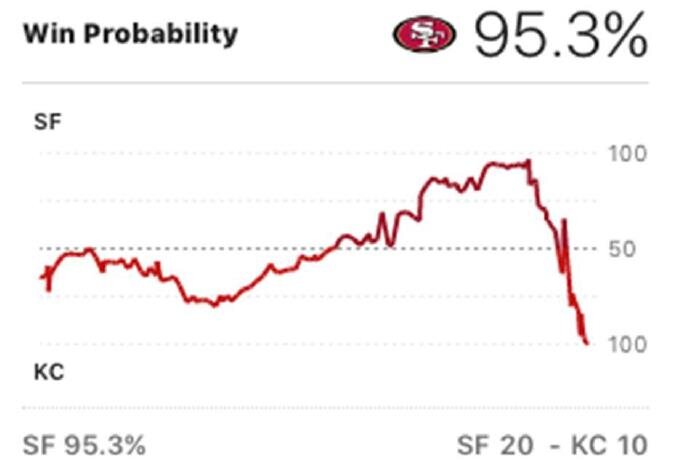

Be wary of forecasts and predictions: Having spent time in January meeting with managers and attending annual meetings and conferences, there is no shortage of predictions of who is going to win the Presidential election in November. The primary purpose of these predictions, it seems, is to make the prognosticator look smart. Moreover, we are struck by the lack of any sense of probabilities in these forecasts. Indeed, future events are presented as near certain outcomes. However, probabilities are not certainties. Just ask the San Francisco 49ers, who enjoyed a 95.3% chance of winning the Super Bowl with only seven minutes left in the fourth quarter:

Source: MSN.com

For all of these reasons, we often tell our analysts to read more history and fewer forecasts. Trying to guess what will happen tomorrow is a fool’s errand; time is better spent understanding what happened yesterday and why, and use that to inform our decisions about tomorrow.

Be critical when it comes to fund returns: A lot of hedge fund managers are congratulating themselves on their performance during the last decade. However, we are skeptical of these reports. In the face of the headwinds affecting the industry – fee compression, a low interest rate environment, less public equity price dispersion, etc. – managers are finding new ways to make money, both for themselves and their investors. In that regard, we believe there are enormous risks in portfolios that investors think are comprised of liquid, public equities. Managers are mixing in private investments to generate returns, promising quarterly or even monthly liquidity when it can take years to unwind some of these positions. All of this reinforces our focus on ongoing due diligence of our current managers. We do not “set it and forget it.” Rather, recognizing our own biases, we try to honestly and dispassionately scrutinize our current managers almost every day to avoid being surprised when returns do not match our expectations.

Due Diligence Tip

As indicated above, we continue to benefit from our relationship with Ambassador Crumpton, his colleagues at Crumpton Group, and his network. They have provided our team with valuable insights into forming conclusions about investment managers based on inputs that go beyond our typical data set (such as track record, references from people who lived or worked with the individual, educational background, upbringing, etc.). Amb. Crumpton talks about “deep intelligence” and frames it in these terms:

At its most elemental, [intelligence] is about understanding and influencing the scope of behavior, from evil to exalted, and maneuvering through this emotional labyrinth in pursuit of valuable information otherwise not available.

- Amb. Henry Crumpton, The Art of Intelligence (2013)

With a foundation of self-awareness (see the previous section of this letter), we can use the tools of intelligence gathering and analysis to increase the degree of confidence of our conclusions about investment managers and opportunities. These can relate to our assessment of an investment manager’s ability to hold a contrarian position, to critically identify weaknesses in a company and use that to establish a short position, or to have the energy required to out-hustle others in a competitive market. The tools also help us form a better view of the manager’s ability to attract and motivate a team, run a good business, and stay engaged over the long term. As we are constantly looking at our due diligence process to “gut check” ourselves to make sure we are asking the right questions, we have found the advice and wisdom in Amb. Crumpton’s book to be particularly useful.

* * *

Market Observations

Indicative of just how easy it was to make money in 2019, we read at the beginning of December 2019, courtesy of Charlie Bilello, that all fifteen major asset classes were positive for the year. Cash, for its part, underperformed all of them. This compares to 2018 when 14 of the 15 asset classes finished lower and cash outperformed everything. What a difference a year makes! Yet, as readers of our letters would anticipate, there are still many things that keep us up at night:

Cyber Attacks – Check Point Research recently issued their 2020 Cyber Security Report, and it included a number of startling statistics and trends that only reinforce our view that cyber attacks remain one of the greatest areas of risk for companies and investors. For instance, the report noted that mobile banking malware jumped 50% in the first half of 2019. The report also included some alarming insights about ransomware: “Rather than immediately deploy a ransomware, offenders often spend weeks exploring the compromised network to locate high-value assets as well as backups, thus maximizing their damage.” Ransomware is a huge and under-reported problem. Municipalities and local governments are known to be at risk, but this chart below shows also how health-care providers (who have some of the most sensitive personally identifiable information) have seen a spike in attacks as well:

Source: Bloomberg

We thought we would share one useful tip to reduce the risk of being hacked: be extremely careful using public charging stations. Known as “juice jacking,” hackers can get into your phone when it is directly connected to a USB port on a charging station, such as at an airport or hotel. To guard against this risk, charge your phone by directly connecting it to a wall socket. Another option is to use a USB data blocker or “juice-jack defender.” These devices are designed to prevent accidental data exchange when your device is plugged into another device with a USB cable.

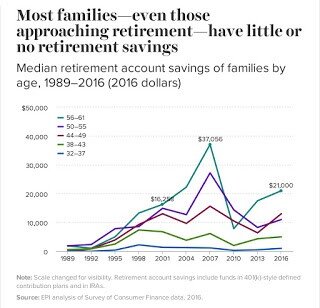

Retirees Without Adequate Savings. The Economic Policy Institute recently issued a report that concluded that Americans ages 56 to 61 had a median balance of $21,000 in their 401(k) accounts in 2016, which is the most up-to-date data on file. With so little set aside for retirement, it did not surprise us to read, according to Maurie Backman at The Motley Fool, that 28% of U.S. adults in their 60’s have less than $50,000 set aside for retirement. Moreover, 13% have only between $50,000 and $99,000. In other words, over 40% of retirees have less than $100,000 in their retirement accounts.

Source: Economic Policy Institute

Almost 10,000 baby boomers turn 65 every day, according to a report by Hunter Kuffel. The boomer retirement wave will affect almost every aspect of the economy, especially Social Security, the job market, healthcare, housing, and consumer spending. For instance, according to Stephen McBride at Mauldin Economics, spending drops on average by 37.5% in retirement. Given that consumption accounts for 70% of US economic activity, this is a major deflationary force. This dynamic, combined with the low savings among retirees, will be a significant headwind for markets over the next twenty years.

China Bond Defaults: With China struggling with its biggest health crisis since 2003, the outlook for Chinese bondholders has become decidedly cloudier over the last several weeks. The lockdown on travel and the temporary closure of many factories and retail outlets as a result of the coronavirus outbreak is only throwing more fuel on the fire.

Source: Bloomberg

As reported in the South China Morning Post, corporate debt swelled to a record 165% of GDP last year. As a result, Chinese policymakers are allowing more bond failures in part to impose increased discipline on borrowers and investors. This should be a good thing long term, but according to Cindy Huang, an analyst at S&P Global Ratings, in the short term, “This will hinder market confidence and weaken the healthy development of China’s credit market.”

SEC Proposes to Ease Auditor Independence Rules. We were surprised to read at the end of the year that the Securities and Exchange Commission is proposing to change the auditor independence rules and relax oversight of audit firms in cases involving affiliates of their clients and preparations for IPOs. This deeply troubles us given the real risk of malfeasance with public company audits. In early February, The Wall Street Journal reported on a criminal investigation of executives’ influence on auditors involving Ernst & Young and alleged big-rigging by executives at Sealed Air Corp. Almost two decades since legal curbs were imposed on management’s oversight of audit firms in the wake of the numerous accounting scandals at the time (Enron etc.), auditor independence is crucial to integrity in the financial markets. Weakening these rules does not seem to be a good idea.

* * *

Closing Thought

We are always mindful of cyber hackers and scammers and try to share tips to reduce the risk of fraud. At the beginning of the year, Ira Rheingold of the National Association of Consumer Advocates, highlighted a novel scheme and a helpful tip that we thought was worth sharing: Do not abbreviate “2020.” When the year 2020 is abbreviated to “20,” it can be manipulated and expose people to fraud. For example, a document dated “2/15/20” can easily be changed to “2/15/2021” simply by adding two numbers to the end. There are various ways this could create a problem. If you sign a credit contract and date it “2/15/20” and then miss a month or two of payments, the lender could add “19” to the end of that date and argue that you owe more than a year's worth of payments. Rheingold also cited the example of a dated check, or one that was written more than six months or so ago. If you have an old check lying around that is dated “2/15/20” and someone finds it, they could add “21” to the end of that date, and now the check is no longer stale. Of course, this relates primarily to payments and legal documents, but one can never be too careful about these types of risks in the digital age.

Finally, we were approached this week by one of our local partners looking for a surgical mask. He was on his way to Brazil and found that masks are hard to come by here in New York. We mention it because, having read our letters for years, he assumed we would be prepared for that contingency. Indeed we were!

We welcome any questions or thoughts you may have.

Sincerely,

Alternative Investment Management, LLC (AIM13)